News Release

Engineer Transforms Personal Experiences into 'Bridges to Education' for Underrepresented Students

San Diego, Calif., Jan. 23, 2020 -- When he was 10 years old, Oscar Vazquez-Mena learned that his ancestors, the ancient Mayans, had once been a technologically advanced culture that excelled in mathematics, astronomy, art and architecture. Yet all around him in Chiapas, his home state in Mexico, families lived in poverty and children did not have access to many educational opportunities.

Now, as an assistant professor of nanoengineering at Â鶹´«Ã½, Vazquez-Mena is working to support the educational development of students from marginalized communities in the United States and across the border.

One of the initiatives he helped build is an academic program for high school students who are U.S. citizens but live in Tijuana and commute across the border each day to attend school because their parents have been deported. The program, called Bridges to Education, provides mentoring, tutoring and workshops in Tijuana to guide both students and their parents in applying for college and financial aid. It also organizes visits to the Â鶹´«Ã½ campus and connects students with summer research positions.

|

| Students from Imperial Valley College visit Vazquez-Mena's lab to get hands-on engineering experience assembling graphene circuits |

“What I’ve seen with students in this program, and something that I’ve also experienced myself, is this fear of not being able to make it to a place where there are not many people like me. Coming from the same background, I can connect with the students to help them overcome this fear, to give them access to more educational resources and encourage them to be confident that they too can do this,” Vazquez-Mena said.

In honor of his work, Vazquez-Mena today was named an Emerging Scholar for 2020 by magazine. He is one of 15 scholars under the age of 40 receiving this recognition. Each scholar is selected based on a number of criteria, including commitment to teaching, community service, research, scholarly awards, honors and academic accomplishments.

Vazquez-Mena grew up in Chiapas, one of the poorest states in Mexico, with one of the largest indigenous populations. After learning about the ancient Mayans in middle school, he became inspired to connect with his ancestral roots in science. No one else in his family was a scientist, save for one uncle. However, his grandfather owned a large collection of science books. “They were all untouched, unread,” Vazquez-Mena said. “Having them was a status symbol.”

These books were the gateway to his future. He would sit in his grandfather’s study for hours flipping through pages about nuclear energy and physics. “At the time I wasn’t really understanding everything, but I still found it all so fascinating. Meanwhile, my mother would be calling me to come out for lunch and I couldn’t pull myself away. That’s when I knew this was my passion,” he said.

|

| Vazquez-Mena (left) working with Vivi Sarmiento (right), a postdoc from the University Autonoma of Baja California, to make graphene nanomaterials. |

By the time he reached high school, Vazquez-Mena knew he wanted to major in physics. He spent most of his time studying and reading and became one of the top students in his school. For college, he attended Monterrey Institute of Technology in Mexico, where he earned a bachelor’s in physics and graduated with honors. Afterwards, he studied abroad in Sweden to earn his master’s in nanoscale science and engineering, then in Switzerland to earn his Ph.D. in microelectronics and microsystems. Later, in 2012, he went to UC Berkeley as a postdoctoral fellow in the physics department, then joined the faculty of Â鶹´«Ã½ in 2015.

Bridging Cultural Barriers

Throughout his career, Vazquez-Mena has not forgotten his people back home. He has made it his mission as a scholar and educator to improve educational access for marginalized people.

“It’s unfortunate that our community is not aware of the rich cultural history of the indigenous people,” he said. “It breaks my heart to see that the kids selling cigarettes on the street or cleaning your shoes don’t know that they share the same blood as people who were doing great things in math and science. In Chiapas, there is not much exposure to science and technology. So growing up there, it’s hard to envision yourself as a scientist.”

Vazquez-Mena mentors Latinx/Chicanx youth by helping them overcome some of the cultural barriers that hold them back from entering STEM and pursuing advanced degrees. For example, there is a common fear to try new things and enter uncharted territory, he noted.

|

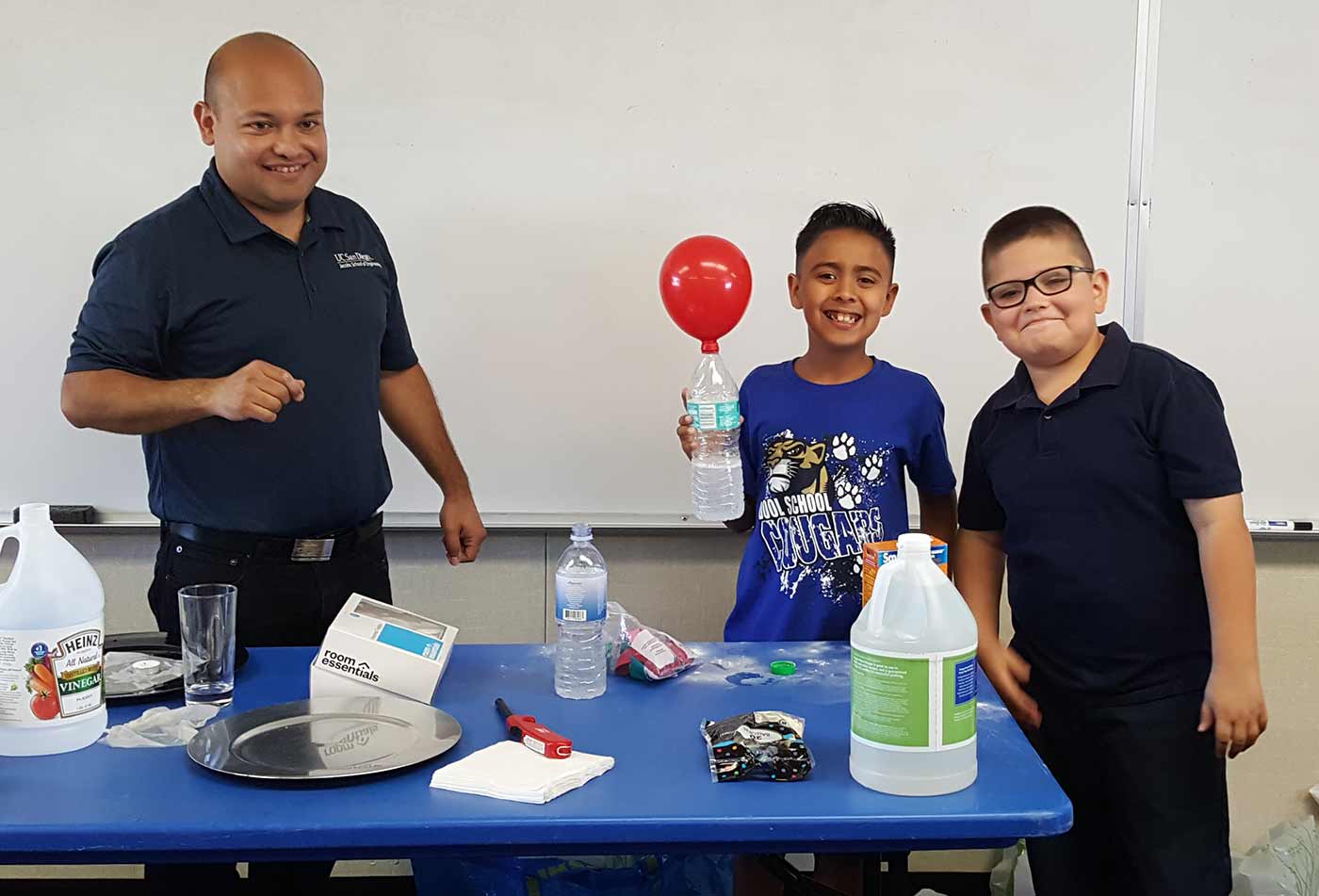

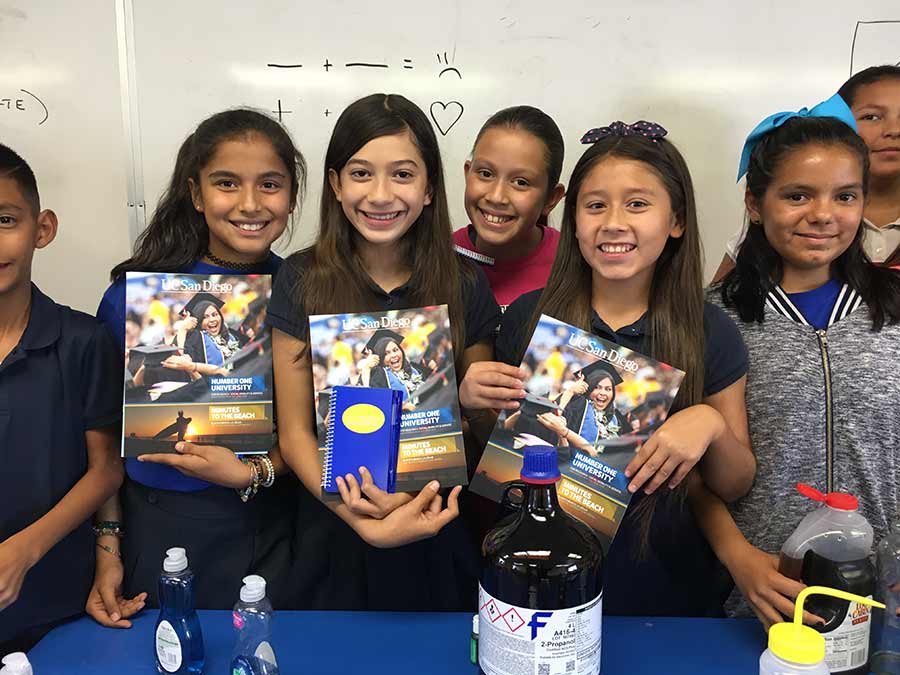

| Vazquez-Mena hosting a science demo at Dool Elementary School in Calexico |

“There’s a difference in how effort is valued in Mexican culture versus in the United States. Here, you get applauded for trying and are encouraged to keep trying if you don’t succeed the first time. But if you grew up in a Mexican community, you may be more hesitant to try because you are afraid others might make fun of you and see you as a failure if it doesn’t work out.”

To combat these preconceptions, Vazquez-Mena encourages students to try, try again. With Bridges to Education, he organizes campus tours so that underrepresented students not only get to see Â鶹´«Ã½ firsthand, but also get some hands-on learning experience. Students participate in interactive workshops at some of the Jacobs School of Engineering maker spaces, where they learn how to use new tools and build devices such as small dancing robots and photodetectors made from nanomaterials. And over the summer, Bridges to Education brings in nearly 20 students to campus to conduct research in various engineering labs, including Vazquez-Mena’s.

|

“When the students come here and see that they did something that is also done by students here at Â鶹´«Ã½, they realize that they can also accomplish new things. I can see in their eyes that they feel more confident and are less fearful about trying things. And I think that even just being here on campus helps them with that,” Vazquez-Mena said.

Another barrier for many of these students is their reluctance to leave their families. Sometimes, there’s even resistance from their parents to let them move away for college. “Family is a very, very important part of Mexican culture. There’s this mindset that the whole family has to stay together, and especially if you’re the eldest kid, you feel an obligation to stay behind and help out. Even my mother still regrets that I left,” Vazquez-Mena said.

The Bridges to Education program works to overcome this barrier by involving parents in its outreach efforts. Through informational workshops in Tijuana, parents get the chance to participate in their children’s mentoring, tutoring and college application processes. The program also counsels parents to help them emotionally and mentally prepare for sending their children off to college.

Bridges for Undergraduates and Transfer Students

One of Vazquez-Mena’s latest outreach efforts is building a STEM partnership with Imperial Valley College. His goal is to help the college serve as a local center for promoting STEM in Imperial Valley County, which is a major agricultural hub. “We hope to expose students in this community to more science and technology,” he said.

|

| A hand-drawn thank you card from Dool Elementary School students is proudly displayed in Vazquez-Mena's office |

Twice a year, Vazquez-Mena organizes Saturday workshops in which 10-20 students from Imperial Valley come to Â鶹´«Ã½ to do hands-on engineering projects, such as building photodetectors or learning to use Arduino microcontrollers. With the help of Â鶹´«Ã½ electrical engineering professor Truong Nguyen and electrical engineering Ph.D. student Phuong Truong from , a student-run program that creates fun, hands-on learning projects to teach students engineering skills, Vazquez-Mena is working to expand the workshops to include more activities and have local companies participate. He is also working with professors at Imperial Valley College so they can implement these workshops on their campus and ultimately start up projects in their own labs to open up more research opportunities for their students.

Vazquez-Mena still has his sights set on expanding his efforts even further. In the future, he would like to put together a program to help Latinx/Chicanx transfer students get into research earlier on.

“There’s so much more that I want to do, so many other communities that I want to connect with and better serve. I am grateful to be at a place like Â鶹´«Ã½ that is so supportive of efforts like this,” he said.

Media Contacts

Liezel Labios

Jacobs School of Engineering

858-246-1124

llabios@ucsd.edu